Solid-fuel rocket

A solid rocket or a solid-fuel rocket is a rocket engine that uses solid propellants (fuel/oxidizer). The earliest rockets were solid-fuel rockets powered by gunpowder; they were used by the Chinese in warfare as early as the 13th century and later by the Mongols, Arabs, and Indians.[1]

All rockets used some form of solid or powdered propellant up until the 20th century, when liquid rockets and hybrid rockets offered more efficient and controllable alternatives. Solid rockets are still used today in model rockets and on larger applications for their simplicity and reliability.

Since solid-fuel rockets can remain in storage for long periods, and then reliably launch on short notice, they have been frequently used in military applications such as missiles. The lower performance of solid propellants (as compared to liquids) does not favor their use as primary propulsion in modern medium-to-large launch vehicles customarily used to orbit commercial satellites and launch major space probes. Solids are, however, frequently used as strap-on boosters to increase payload capacity or as spin-stabilized add-on upper stages when higher-than-normal velocities are required. Solid rockets are used as light launch vehicles for low Earth orbit (LEO) payloads under 2 tons or escape payloads up to 1000 pounds.[2][3]

Contents |

Basic concepts

A simple solid rocket motor consists of a casing, nozzle, grain (propellant charge), and igniter.

The grain behaves like a solid mass, burning in a predictable fashion and producing exhaust gases. The nozzle dimensions are calculated to maintain a design chamber pressure, while producing thrust from the exhaust gases.

Once ignited, a simple solid rocket motor cannot be shut off, because it contains all the ingredients necessary for combustion within the chamber in which they are burned. More advanced solid rocket motors can not only be throttled but also be extinguished and then re-ignited by controlling the nozzle geometry or through the use of vent ports. Also, pulsed rocket motors that burn in segments and that can be ignited upon command are available.

Modern designs may also include a steerable nozzle for guidance, avionics, recovery hardware (parachutes), self-destruct mechanisms, APUs, controllable tactical motors, controllable divert and attitude control motors, and thermal management materials.

Design

Design begins with the total impulse required, which determines the fuel/oxidizer mass. Grain geometry and chemistry are then chosen to satisfy the required motor characteristics.

The following are chosen or solved simultaneously. The results are exact dimensions for grain, nozzle, and case geometries:

- The grain burns at a predictable rate, given its surface area and chamber pressure.

- The chamber pressure is determined by the nozzle orifice diameter and grain burn rate.

- Allowable chamber pressure is a function of casing design.

- The length of burn time is determined by the grain 'web thickness'.

The grain may or may not be bonded to the casing. Case-bonded motors are more difficult to design since the deformation of the case and the grain under flight must be compatible.

Common modes of failure in solid rocket motors include fracture of the grain, failure of case bonding, and air pockets in the grain. All of these produce an instantaneous increase in burn surface area and a corresponding increase in exhaust gas and pressure, which may rupture the casing.

Another failure mode is casing seal design. Seals are required in casings that have to be opened to load the grain. Once a seal fails, hot gas will erode the escape path and result in failure. This was the cause of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster.

Grain geometry

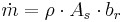

Solid rocket fuel deflagrates from the surface of exposed propellant in the combustion chamber. In this fashion, the geometry of the propellant inside the rocket motor plays an important role in the overall motor performance. As the surface of the propellant burns, the shape evolves (a subject of study in internal ballistics), most often changing the propellant surface area exposed to the combustion gases. The mass flux (kg/s) [and, therefore, pressure] of combustion gases generated is a function of the instantaneous surface area  , (m2), and linear burn rate

, (m2), and linear burn rate  (m/s):

(m/s):

Several geometric configurations are often used depending on the application and desired thrust curve:

- Circular Bore: if in BATES configuration, produces progressive-regressive thrust curve.

- End Burner: propellant burns from one axial end to other producing steady long burn, though has thermal difficulties, CG shift.

- C-Slot: propellant with large wedge cut out of side (along axial direction), producing fairly long regressive thrust, though has thermal difficulties and asymmetric CG characteristics.

- Moon Burner: off-center circular bore produces progressive-regressive long burn, though has slight asymmetric CG characteristics

- Finocyl: usually a 5- or 6-legged star-like shape that can produce very level thrust, with a bit quicker burn than circular bore due to increased surface area.

Casing

The casing may be constructed from a range of materials. Cardboard is used for small black powder model motors, whereas aluminum is used for larger composite-fuel hobby motors. Steel is used for the space shuttle boosters. Filament wound graphite epoxy casings are used for high-performance motors.

The casing must be designed to withstand the pressure and resulting stresses of the rocket motor, possibly at elevated temperature. For design, the casing is considered a pressure vessel.

To protect the casing from corrosive hot gases, a sacrificial thermal liner on the inside of the casing is often implemented, which ablates to prolong the life of the motor casing.

Nozzle

A convergent-divergent design accelerates the exhaust gas out of the nozzle to produce thrust. The nozzle must be constructed from a material that can withstand the heat of the combustion gas flow. Often, heat-resistant carbon-based materials are used, such as amorphous graphite or carbon-carbon.

Some designs include directional control of the exhaust. This can be accomplished by gimballing the nozzle, as in the Space Shuttle SRBs, by the use of jet vanes in the exhaust similar to those used in the V-2 rocket, or by liquid injection thrust vectoring (LITV).

An early Minuteman first stage used a single motor with four gimballed nozzles to provide pitch, yaw, and roll control.

LITV consists of injecting a liquid into the exhaust stream after the nozzle throat. The liquid then vaporizes, and in most cases chemically reacts, adding mass flow to one side of the exhaust stream and thus providing a control moment. For example, the Titan IIIC solid boosters injected nitrogen tetroxide for LITV; the tanks can be seen on the sides of the rocket between the main center stage and the boosters.[4]

Performance

A typical well designed ammonium perchlorate composite propellant (APCP) first stage motor may have a vacuum specific impulse (Isp) as high as 285.6 s (Titan IVB SRMU).[5] This compares to 339.3 s for kerosene/liquid oxygen (RD-180)[6] and 452.3 s for hydrogen/oxygen (Block II SSME)[7] bipropellant engines. Upper stage specific impulses are somewhat greater: as much as 303.8 s for APCP (Orbus 6E),[8] 359 s for kerosene/oxygen (RD-0124)[9] and 465.5 s for hydrogen/oxygen (RL10B-2).[10] Propellant fractions are usually somewhat higher for (non-segmented) solid propellant first stages than for upper stages. The 117,000 pound Castor 120 first stage has a propellant mass fraction of 92.23% while the 31,000 pound Castor 30 upper stage recently developed for Orbital Science's Taurus II COTS (International Space Station resupply) launch vehicle has a 91.3% propellant fraction with 2.9% graphite epoxy motor casing, 2.4% nozzle, igniter and thrust vector actuator, and 3.4% non-motor hardware including such things as payload mount, interstage adapter, cable raceway, instrumentation, etc. Castor 120 and Castor 30 are 93 and 92 inches in diameter, respectively, and serve as stages on the Athena IC and IIC commercial launch vehicles. A four stage Athena II using Castor 120s as both first and second stages became the first commercially developed launch vehicle to launch a lunar probe (Lunar Prospector) in 1998.

Solid rockets can provide high thrust for relatively short periods of time. For this reason, solids have been used as initial stages in rockets (the classic example being the Space Shuttle), while reserving high specific impulse engines, especially less massive hydrogen fueled engines for higher stages. In addition, solid rockets have a long history as the final boost stage for satellites due to their simplicity, reliability, compactness and reasonably high mass fraction.[11] A spin-stabilized solid rocket motor is sometimes added when extra velocity is required, such as for a mission to a comet or the outer solar system, because a spinner does not require a guidance system (on the newly added stage). Thiokol's extensive family of mostly titanium-cased Star space motors has been widely used, especially on Delta launch vehicles and as spin-stabilized upper stages to launch satellites from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle. Star motors have propellant fractions as high as 94.6% but add-on structures and equipment reduce the operating mass fraction by 2% or more.

Higher performing solid rocket propellants are used in large strategic missiles (as opposed to commercial launch vehicles). HMX, C4H8N4(NO2)4, a nitramine with greater energy than ammonium perchlorate, is the main ingredient in NEPE-75 propellant used in the Trident II D-5 Fleet Ballistic Missile.[12] It is because of explosive hazard that the higher energy military solid propellants are not used in commercial launch vehicles except when the LV is an adapted ballistic missile already containing HMX propellant (example: Minotaur IV and V based on retired Peacekeeper ICBMs).[13] The Naval Air Weapons Station at China Lake, CA developed a new compound, C6H6N6(NO2)6, called simply CL-20 (China Lake compound #20). Compared to HMX, CL-20 has 14% more energy per mass, 20% more energy per volume, and a higher oxygen-to-fuel ratio.[14] One of the motivations for development of these very high energy density military solid propellants is to achieve mid-course exo-atmospheric ABM capability from missiles small enough to fit in existing ship-based below-deck vertical launch tubes and air-mobile truck-mounted launch tubes. CL-20 propellant compliant with Congress' 2004 insensitive munitions (IM) law has been demonstrated and may, as its cost comes down, be suitable for use in commercial launch vehicles, with a very significant increase in performance compared with the currently favored APCP solid propellants.

An attractive attribute for military use is the ability for solid rocket propellant to remain loaded in the rocket for long durations and then reliably launched at a moment's notice.

Propellant families

Black Powder (BP) Propellants

Composed of charcoal (fuel), potassium nitrate (oxidizer), and sulfur (additive), black powder is one of the oldest pyrotechnic compositions with application to rocketry. In modern times, black powder finds use in low-power model rockets (such as Estes and Quest rockets), as it is cheap and fairly easy to produce. The fuel grain is typically a mixture of pressed fine powder (into a solid, hard slug), with a burn rate that is highly dependent upon exact composition and operating conditions. Due to its sensitivity to fracture (and, therefore, catastrophic failure upon ignition) and poor performance (specific impulse around 80 s), BP does not typically find use in motors above 40 Ns.

Zinc-Sulfur (ZS) Propellants

Composed of powdered zinc metal and powdered sulfur (oxidizer), ZS or "micrograin" is another pressed propellant that does not find any practical application outside of specialized amateur rocketry circles due to its poor performance (as most ZS burns outside the combustion chamber) and incredibly fast linear burn rates on the order of 2 m/s. ZS is most often employed as a novelty propellant as the rocket accelerates extremely quickly, leaving a spectacular large orange fireball behind it.

"Candy" propellants

In general, candy propellants are an oxidizer (typically potassium nitrate) and a sugar fuel (typically dextrose, sorbitol, or sucrose) that are cast into shape by gently melting the propellant constituents together and pouring or packing the amorphous colloid into a mold. Candy propellants generate a low-medium specific impulse of roughly 130 s and, thus, are used primarily only by amateur and experimental rocketeers.

Double-Base (DB) Propellants

DB propellants are composed of two monopropellant fuel components where one typically acts as a high-energy (yet unstable) monopropellant and the other acts as a lower-energy stabilizing (and gelling) monopropellant. In typical circumstances, nitroglycerin is dissolved in a nitrocellulose gel and solidified with additives. DB propellants are implemented in applications where minimal smoke is required yet medium-high performance (Isp of roughly 235 s) is required. The addition of metal fuels (such as aluminum) can increase the performance (around 250 s), though metal oxide nucleation in the exhaust can turn the smoke opaque.

Composite propellants

A powdered oxidizer and powdered metal fuel are intimately mixed and immobilized with a rubbery binder (that also acts as a fuel). Composite propellants are often either ammonium nitrate-based (ANCP) or ammonium perchlorate-based (APCP). Ammonium nitrate composite propellant often uses magnesium and/or aluminum as fuel and delivers medium performance (Isp of about 210 s) whereas Ammonium Perchlorate Composite Propellant often uses aluminum fuel and delivers high performance (vacuum Isp up to 296 s with a single piece nozzle or 304 s with a high area ratio telescoping nozzle).[8] Composite propellants are cast, and retain their shape after the rubber binder, such as Hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene (HTPB), cross-links (solidifies) with the aid of a curative additive. Because of its high performance, moderate ease of manufacturing, and moderate cost, APCP finds widespread use in space rockets, military rockets, hobby and amateur rockets, whereas cheaper and less efficient ANCP finds use in amateur rocketry and gas generators. Ammonium dinitramide, NH4N(NO2)2, is being considered as a 1-to-1 chlorine-free substitute for ammonium perchlorate in composite propellants. Unlike ammonium nitrate, ADN can be substituted for AP without a loss in motor performance.

In 2009, a group succeeded in creating a propellant of water and nanoaluminum (ALICE).

The Constellation program uses a mix of aluminum, ammonium perchlorate, a polymer of polybutadiene and acrylonitrile, epoxy and iron oxide.[15]

High-Energy Composite (HEC) propellants

Typical HEC propellants start with a standard composite propellant mixture (such as APCP) and add a high-energy explosive to the mix. This extra component usually is in the form of small crystals of RDX or HMX, both of which have higher energy than ammonium perchlorate. Despite a modest increase in specific impulse, implementation is limited due to the increased hazards of the high-explosive additives.

Composite Modified Double Base propellants

Composite modified double base propellants start with a nitrocellulose/nitroglycerin double base propellant as a binder and add solids (typically ammonium perchlorate and powdered aluminum) normally used in composite propellants. The ammonium perchlorate makes up the oxygen deficit introduced by using nitrocellulose, improving the overall specific impulse. The aluminum also improves specific impulse as well as combustion stability. High performing propellants such as NEPE-75 used in Trident II D-5, replace most of the AP with HMX, further increasing specific impulse. The mixing of composite and double base propellant ingredients has become so common as to blur the functional definition of double base propellants.

Minimum-signature (smokeless) propellants

One of the most active areas of solid propellant research is the development of high-energy, minimum-signature propellant using CL-20 (China Lake compound #20), C6H6N6(NO2)6, which has 14% higher energy per mass and 20% higher energy density than HMX. The new propellant has been successfully developed and tested in tactical rocket motors. The propellant is non-polluting: acid free, solid particulates free, and lead free. It is also smoke free and has only a faint shock diamond pattern that is visible in the otherwise transparent exhaust. Without the bright flame and dense smoke trail produced by the burning of aluminized propellants, these smokeless propellants all but eliminate the risk of giving away the positions from which the missiles are fired. The new CL-20 propellant is shock-insensitive (hazard class 1.3) as opposed to current HMX smokeless propellants which are highly detonable (hazard class 1.1). CL-20 is considered a major breakthrough in solid rocket propellant technology but has yet to see widespread use because costs remain high.[14]

Hobby and amateur rocketry

Solid propellant rocket motors can be bought for use in model rocketry; they are normally small cylinders of black powder fuel with an integral nozzle and sometimes a small charge that is set off when the propellant is exhausted after a time delay. This charge can be used to trigger a camera, or deploy a parachute. Without this charge and delay, the motor may ignite a second stage (black powder only).

In mid- and high-power rocketry, commercially made APCP motors are widely used. They can be designed as either single-use or reloadables. These motors are available in impulse ranges from "D" to "O", from several manufacturers. They are manufactured in standardized diameters, and varying lengths depending on required impulse. Standard motor diameters are 18, 24, 29, 38, 54, 75, 98, and 150 millimeters. Different propellant formulations are available to produce different thrust profiles, as well as "special effects" such as colored flames, smoke trails, or large quantities of sparks (produced by adding titanium sponge to the mix).

Designing solid rocket motors is particularly interesting to amateur rocketry enthusiasts. The design of a successful solid-fuel motor requires application of continuum mechanics, combustion chemistry, materials science, fluid dynamics (including compressible flow), heat transfer, geometry (particle spectrum packing), and machining. The vast majority of amateur-built rocket motors utilize a composite propellant, most commonly APCP.

History

Solid rockets were invented by the Chinese, the earliest versions were recorded in the 13th century. Hyder Ali, king of Mysore, developed war rockets with an important change: the use of metal cylinders to contain the combustion powder. Castable solid rockets engines were invented by John Whiteside Parsons when he replaced black powder with asphalt and potassium perchlorate to give a much higher Isp.

Advanced research

- Environmentally sensitive fuel formulations such as ALICE propellant

- Ramjets with solid fuel

- Variable thrust designs based on variable nozzle geometry

- Hybrid rockets that use solid fuel and throttleable liquid or gaseous oxidizer

See also

- Fireworks

- Pyrotechnic composition

- Ammonium Perchlorate Composite Propellant

- Intercontinental ballistic missile

- Jetex engine

- Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster

- Skyrocket

- Comparison of solid-fuelled orbital launch systems

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ^ chapters 1–2, Blazing the trail: the early history of spacecraft and rocketry, Mike Gruntman, AIAA, 2004, ISBN 1-56347-705-X.

- ^ www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/LADEE/main

- ^ www.space-travel.com/reports/LockMart_And_ATK_Athena_Launch_Vehicles_Selected_As_A_NASA_Launch_Services_Provider_999.html

- ^ Sutton, George P. (2000). Rocket Propulsion Elements; 7 edition. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-32642-9.

- ^ ATK Space Propulsion Products Catalog, May 2008, p. 30

- ^ www.pw.utc.com/Products/Pratt+%26+Whitney+Rocketdyne/Propulsion+Solutions/Space

- ^ www.pw.utc.com/Products/Pratt+%26+Whitney+Rocketdyne

- ^ a b www.spaceandtech.com/spacedata/elvs/titan4b_specs.shtml

- ^ www.russianspaceweb.com/engines/rd0124.htm

- ^ www.pw.utc.com/StaticFiles/Pratt%20.../Products/.../pwr_rl10b-2.pdf

- ^ Solid

- ^ www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/systems/d-5-features.htm

- ^ Minotaur IV User's Guide, Release 1.0, Orbital Sciences Corp., January 2005,p. 4

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (August 30, 2010). "NASA Tests Engine With an Uncertain Future". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/31/science/space/31rocket.html?hpw. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

External links

- Robert A. Braeunig rocket propulsion page

- Astronautix Composite Solid Propellants

- Ariane 5 SRB

- Amateur High Power Rocketry Association

- Nakka-Rocketry (Design Calculations and Propellant Formulations)

- 5 cent sugar rocket

- Practical Rocketry

- NASA Practical Rocketry

- The short film Big Picture: Solid Punch is available for free download at the Internet Archive [more]